By Emma Brown and Jacob Fenston

Washington Post Staff Writer and Special to The Washington Post

Sunday, September 20, 2009

We were coated in a slick of sweat, diesel exhaust and sunscreen when we coasted up to a man wearing just-shined shoes and drinking rum from a plastic cup. He squinted at our crinkled map, nodded, told us we wanted to go south to the beach at San Luis and walked off as we tried to explain that we were headed north.

Next we tried an older woman, who donned her huge reading glasses to examine the map. She held it upside down and agreed that San Luis was probably where we were headed. Her nephew chimed in: Nothing up that other road but mountains and rivers. “Do what you want,” he said, exasperated. “But you won’t get there before dark.”

It was Day 3 of our self-guided biking tour of Cuba. We were lost, and everyone — including a baseball team playing by the side of the road — was trying to help.

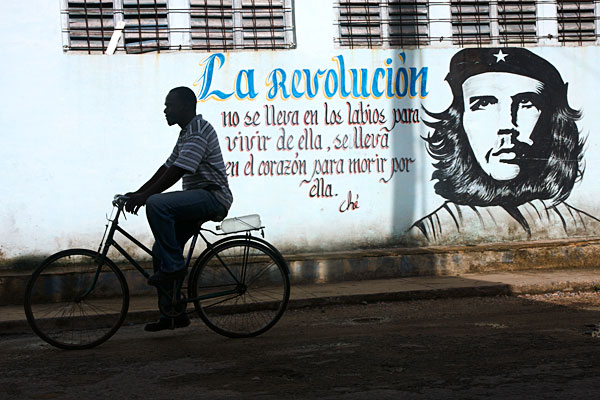

We had arrived in Cuba on a late-night flight from San Jose, Costa Rica, staying that first night in the home of a friendly, fast-talking couple who rented us a room in their bright blue Havana apartment and kindly stored our bicycle boxes until our return seven days later. Pedaling west out of the city, along its famed seaside promenade, we had passed apartment buildings hung with laundry, crumbling grand hotels and nationalist slogans (“¡Viva Castro! ¡Patria o muerte!”) scrawled on pieces of wood and nailed to telephone poles.

Now we were somewhere in Pinar del Rio province, the country’s tobacco capital. We’d taken a wrong turn and were trying to find a shortcut back to our route, where our guidebook said we’d find a small guesthouse that had a tendency to fill up fast.

We didn’t have reservations or a phone number, but we crossed our fingers, turning down a dirt road that didn’t appear on the map. The sky, which had been darkening all day, cracked open, unleashing bolts of lightning and sheets of rain. We hunched our shoulders, pedaled faster and — what else could we do? — laughed.

Traveling on two wheels in Cuba, we were discovering, means being exposed to the weather. But it also means being exposed to the country — its hidden valleys, its roadside fried-chicken vendors, its tucked-away-in-a-courtyard music — in a way we might not otherwise be.

Soaked and shivering late that rainy afternoon, we finally rolled up to Finca la Guabina, a horse ranch that doubles as an eco-hotel. A young woman who seemed to operate the place by herself offered us a luckily vacant room in the high-ceilinged converted farmhouse, where a flier beside the bed boasted such attractions as horseback riding, cockfighting and crocodile-breeding.

We opted instead for hot showers and cold mojitos and fell into bed exhausted, listening to the occasional shriek of a peacock that made its night home on a trellis outside our window.

* * *

When the Soviet Union fell nearly two decades ago, Cuba scrambled to make up for lost subsidies, and tourism became one of the country’s most reliable sources of hard currency. President Fidel Castro legalized the U.S. dollar and eased restrictions on foreign investment; hotels mushroomed and Cubans started renting out rooms in their homes. Now, despite the U.S. embargo that prohibits most Americans from spending money here, Cuba is the Caribbean’s second most popular destination (after the Dominican Republic), with picturesque spots flooded with vacationing Europeans and Canadians.

Cubans we met were curious about these two Americans on bikes, and they had lots of friendly questions about baseball, Barack Obama, the economic crisis and hip-hop. (“Wow, I never met an American guy,” said a man with dreadlocks whom we met in a Havana cafe. “Do you like Tupac?”)

With a license from the Treasury Department, it’s possible to travel to the island legally for journalism, academic research or professional meetings. Otherwise, going to Cuba requires patience with the layers of inconvenience that come with skirting the embargo. We saw no other Americans during our week-long trip.

We traveled for a full day, flying from Washington to Houston to Costa Rica — where we spent a seven-hour layover — and finally to Havana.

Bringing bikes in cardboard boxes made the journey even more of a hassle. But we thought it would be worth it: Touring the island by bike would give us a measure of independence. And it would give us a sort of behind-the-scenes look at this country, where cars are a rare luxury and workers commute by foot, horse-drawn wagon, bus, bici-taxi or bike.

Cuba’s embrace of non-motorized transit is no accident, and it’s fairly new. At the same time that Castro was building hotels in the early ’90s, he was also buying bikes: Fuel imports had crashed with the Communist bloc, buses had stopped running, and people needed a way to get around. The country imported 2 million bikes from China and sold them at subsidized prices. Local factories churned out 150,000 bikes a year, and bike lanes appeared in cities and towns across the country.

But as tourism has grown and the economy has rebounded, cars and buses have begun edging out bicycles again. And already, President Obama has signaled that he is open to reestablishing diplomatic ties, loosening travel restrictions for Cuban Americans and allowing them to send more money to family. Should the embargo be lifted, the number of tourists visiting the country would double, according to the International Monetary Fund. This might be the perfect time to go biking in Cuba, before cars take back the streets.

* * *

The next morning, our lonely-seeming hotelier served us a hefty plate of fresh mango and pineapple for breakfast and told us not to worry about the chunks of dried mud our bikes had shed in her lobby. We pedaled away from the ranch in the slanting light of sunrise, flanked by galloping horses (and perhaps, slithering just out of view, breeding crocodiles).

A long day lay ahead: Our circuitous, took-a-wrong-turn route meant that we had covered a mere 12 miles the day before. That left us with nearly 100 miles to our next destination, Maria la Gorda, a white-sand beach at the island’s western tip.

We rolled through valleys past mountainous rock formations called mogotes, and through tiny towns in the hills where we snacked on eight-cent strawberry ice cream.

In a tiny, cramped store selling an assortment of imported goods — shampoo, juice, one bicycle tire — we waited to buy bottled water in a slow-moving line that snaked toward a counter manned by a sole cashier. The line was full of women who seemed at first not to notice the sweaty, spandex-clad foreigners impatient to get back on the road. But then an older woman with kind eyes turned toward us.

“It’s boring for us, too,” she said. A younger woman near the front of the line took pity on us and pushed us up to the counter ahead of her, where we scored our cold water.

Cuba is a cyclist’s paradise: Many roads are empty, and even on the busiest highways, drivers are used to sharing with bikes, pedestrians, horses, mules and anything else that can roll or walk.

After lunch it felt more like a cyclist’s hell: hot, flat and unending, with not a spot of shade for miles.

The monotony of the parched western end of the island was finally broken when we entered Guanahacabibes National Park, a UNESCO biosphere reserve where a dense, humid forest surrounds the narrow road. Land crabs scuttled in leaves at the pavement’s edge, and we dodged thousands that had bravely ventured out onto asphalt — shrieking, we admit, when they raised their little claws as if to grab our tires, wrangle us to the ground and pluck out our eyeballs.

The forest broke suddenly into beach, and we caught our first glimpse of the Caribbean Sea, as gloriously blue as postcards promise. We rode another hour, tracing the coast until the road ended at a sleepy, palm-studded resort. Inside the thatch-roofed lobby, a clerk greeted us in perfect British English, gave us our room key and told us that the all-you-can-eat buffet was already open for dinner.

There’s something undeniably lovely about sleeping late and lounging in the sand and giving saddle sores a chance to heal; we had been looking forward to it for days. But in what is perhaps an unhealthy reaction to the chance to relax, we grew antsy. Surrounded by pink Germans and Dutch marooned on white plastic beach chairs, we realized that there’s a fine line between lounging and languishing.

After a day of sun, sea and sand, we headed back toward Havana. We didn’t have time to ride, so we bungeed our bikes to the roof of a taxi. As we sped past homesteads carved out of the tropical forest, with pigs and goats tied in front, we asked the driver whether Cubans resent Americans for the hardships caused by the 49-year-old embargo.

“No, no, not at all,” he answered. “It’s a thing between two governments — it’s not the people’s fault.” In fact, he said, Cubans want more Americans to visit.

“Why?”

“Because they bring a lot of money.”

He earned the equivalent of $12 a month working for the state-run taxi company, he said. With salaries like that, everyone in Cuba has to hustle to get by.

Traveling by bus or taxi is different from biking. You’re protected from the elements — the rain and the mud, and also the small-time entrepreneurs trying to sell you a cigar or a pineapple — but missing those things seems to be missing Cuba itself.

Back in Havana, our hosts Humberto and Kary pulled out our bike boxes, and we disassembled the filthy machines. We asked Humberto where we could buy more packing tape. He said it’s hard to find; in Cuba, you can’t just go out and buy something when you need it. But he insisted on getting it for us. Hours later, there was a new roll of tape in our room. He’d spent much of the afternoon hunting it down.

For our last night, we thought we might splurge on dinner and followed our guidebook to a restaurant described as “one of the most romantic settings on planet earth,” in a plaza next to a baroque cathedral. It was pretty and overpriced, with chewy fish and a waitress who seemed tired of tourists.

We thought back to our nights after biking — our huge appetites, and the home-cooked meals provided by people from whom we’d rented rooms. Our best dinner — and best room — was in a town called Cabanas, which has no government-sanctioned (i.e., tax-paying) place to stay. The only way to find one is to show up and wait. We sat on a cement bench in the town plaza for three minutes before a man in a baseball cap and tank top approached. He led us up the hill to an idyllic little place where a couple and their young daughter gave us food they’d grown on their neighboring farm.

In the morning, our taxi to the airport honked, and Humberto held the door open as we lugged our bike boxes down two flights of stairs. He shook our hands and wished us a good trip home. “And may you have 40 more years of cycling,” he added, making cranking motions with his hands.